In the last month, there has been a huge increase in COVID-19 related addiction news. Although the current situation is unprecedented, many of the policy responses have well-established precedents including forms of prohibition, regulation and outreach treatment. Perhaps the most common policy option has been to ban substances, particularly alcohol.

Alcohol

Several countries have banned alcohol sales, offering many different reasons for doing so. Some countries have banned alcohol to deter gatherings of people, some to prevent social disorder based on the assumption that intoxicated people struggle more (or worry less?) about staying 2 meters away from other people. In Hong Kong it was the necessity of removing one’s face mask in order to drink that aided their decision to close bars. Nuuk, the capital city of Greenland banned alcohol sales to protect children from alcohol related abuse.

The UK and other countries have allowed alcohol shops to stay open. In the UK this has, by default, conferred an ‘essential service’ status to off-licences, a decision that gives some pause for thought.

Among those countries where alcohol is still permitted, many have reported increased demand. Some people have stockpiled alcohol in preparation for lock-down, some have transferred their drinking from bars to home settings and some are drinking more. A survey in the UK recently suggested that people were doing different things (as people are wont to do) with one-fifth reporting that they had increased, one-third that they had reduced or managed, and around one-in-twenty reporting that they had quit alcohol since COVID-19 lock-down measures were put in place.

In Sri Lanka, prohibition has seen an increase in illicit distilleries making moonshine. An illicit alcohol trade is a population response to alcohol bans for which there is plenty of historical precedent. Attempts to stop moonshine production in Sri Lanka have been hampered by a short-staffed regulatory department that cannot conduct surprise inspections without breaking social distancing rules.

Consuming illicit alcohol can be fatal, and in Iran over 700 people have died from methanol alcohol consumption following false reports that strong or industrial alcohol can cure COVID-19.

Moonshine distillery

Tobacco

Some countries, including Botswana and India, have banned sales of tobacco products to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Their reasoning? Partly because of perceived transmission risks among smokers (all that face-touching, perhaps), and partly because those who smoke are more likely to have pre-existing health conditions that could increase the risk of developing serious health problems from COVID-19.

The Indian state of Jharkhand has banned public use of all tobacco products, partly to deter people from the spitting associated with products such as gutka.

In line with many other governments, the Botswana government turned to expert advice, and stated that their ban on tobacco sales was based on evidence of harm and lung disease. The evidence to which they refer is not new, smoking has always caused harm. Implementing restrictions on tobacco sales at this time, raises questions about the long-term global response to the 8 million annual deaths from smoking. A number that repeats annually, and that has done so for decades.

Gambling

There are concerning signs from Australia where online gambling has increased by as much as two-thirds since the beginning of lock-down, with many addiction treatment services worried about the combination of stress and 24hr access to online betting platforms.

Most gambling has moved from betting shops, casinos and machines to online settings. This transfer might have been relatively straight-forward for those who use slot-machines; however, those who bet on sports have been doubly stumped as most major sporting events have been cancelled. Responses have been creative, including an increase in betting on non-sporting events, such as fluctuations in exchange rates. The differences between gambling and global finance have never been more blurred.

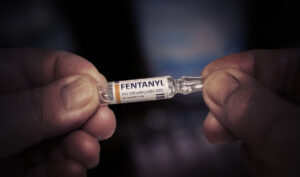

The US opioid epidemic

In the US, before COVID-19 (you remember that time?), the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) regularly reduced fentanyl production through a system of annual supply quotas. In December 2019 they reduced the quota by 30%. In April 2020 they removed the cap on fentanyl production because of its role in ventilating patients with COVID-19.

Meanwhile, US opioid related litigation has largely stalled. While lawsuits are likely to resume when ‘this is all over’, an indeterminate interruption to legal proceedings against pharmaceutical companies for their role in the US opioid epidemic will undoubtedly be welcome news for many executives.

The impact of COVID-19 on drug use and addiction will, of course, be difficult to assess until long after lock-down has been lifted, court cases resumed and off-licences and betting shops re-opened. Addiction research, treatment and evidence informed policy will be vital in preventing harms to some of the most vulnerable and at-risk groups. Groups with vulnerabilities for which there are well-established precedents.

Rob Calder is the deputy web editor for the SSA and Addiction News editor for the journal Addiction.

Addiction News is a searchable collection of global addiction related news. It is updated weekly and welcomes suggestions and contributions from readers.

The SSA does not endorse nor guarantee the accuracy of the information in external sources or links, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of such information

Every effort is made to maintain the accuracy of the information on the SSA website. However, things change all the time. If you discover any out-of-date links or if you know of other links that could be included, please let us know.