When women drink during pregnancy, alcohol is passed to the embryo or fetus through the placenta. Could this fleshy structure that provides oxygen and nutrients be the key to understanding why alcohol can sometimes cause irreversible harm, and other times cause no discernible harm?

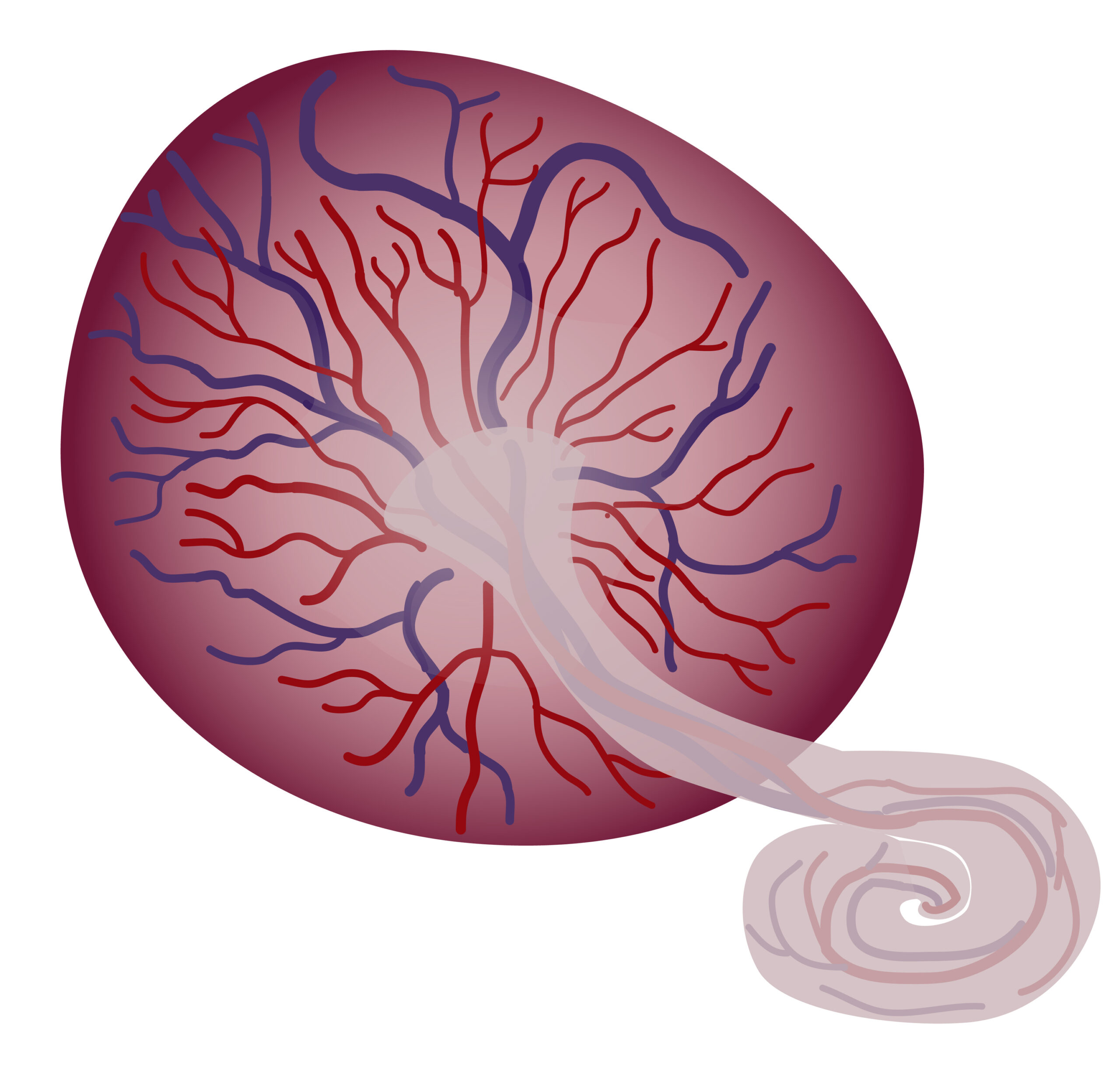

The placenta is a temporary organ that develops at the stage of human reproduction when the embryo attaches to the wall of the uterus. It performs multiple functions during pregnancy, and basically “plays the role of many organs” – for example, the liver, kidney, respiratory, and endocrine systems. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development called the placenta “the least understood human organ and arguably one of the more important, not only for the health of a woman and her fetus during pregnancy but also for the lifelong health of both.”

When pregnant women drink alcohol, it is passed to the embryo or fetus through the placenta. At this point, so early in the lifecourse, alcohol is a hostile substance and can adversely affect the development of the embryo/fetus. One of the most concerning potential consequences of prenatal alcohol exposure is fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), a group of lifelong behavioural, cognitive and physical disabilities.

Preventing FASD is simple on paper: women should not drink during pregnancy. In recent years, public health experts have pursued this goal of eliminating risk rather than reducing harm. The British Medical Association, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and Chief Medical Officers advise women to completely abstain from alcohol if they are pregnant or could get pregnant. In practice, however, the risk lingers, because there are numerous reasons why pregnant women may drink (or continue to drink) during pregnancy. This includes women having pre-existing problems with alcohol, not knowing they are pregnant, and using alcohol to cope with the consequences or symptoms of unresolved trauma and mental health problems.

Research also suggests that the risk of FASD may differ from woman to woman; from pregnancy to pregnancy. According to the British Medical Association, alcohol-related harm commensurate with FASD may be dependent on the level and pattern of alcohol consumption, the stage of pregnancy when alcohol was consumed, and individual factors such as stress during pregnancy.

Another potential mediating factor that hasn’t been fully investigated is the placenta. This under-appreciated organ might help to account for the apparent unpredictability of disability caused by drinking during pregnancy, and explain why it is not (yet) possible for experts to determine a ‘safe’ level of drinking.

Much of what has been gathered to date about its effect comes from small studies and clinical case reports of monozygotic and dizygotic twins (1 2 3 4 5 6 7) and animal studies (1 2). One suggestion from this research is that each placenta metabolises alcohol differently, and therefore would allow different amounts of ethanol to transfer across into the fetus. This offers a plausible explanation as to why two women could drink the same amounts in pregnancy, but fetal exposure to alcohol and fetal harms from alcohol could be very different.

In addition to researching its “role in mediating ethanol-induced fetal damage”, there is also scope for using the placenta to aid early detection of fetal abnormalities, which could be enormously helpful considering the under-diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and the difficulty drawing conclusions about alcohol-related harm from alcohol consumption in pregnancy (1 2 3):

“The placenta may serve as a medium for early detection and subsequent intervention for deficits where detection may be invasive, inaccessible, or not apparent until later in life, as is the case with many alcohol-induced neurobehavioral abnormalities”.

The placenta remains the “least understood, and least studied, of all human organs”. The Human Placenta Project was borne from the need to better understand placental development, function, and structure throughout all stages of pregnancy, and develop safe, effective ways to assess placental health in real time. The National Institutes of Health in the United States have invested more than $46 million in the project to date. Going forward, “the success of the project [will rely] on collaborations among creative thinkers from many different fields — from obstetrics and placental biology to bioengineering and data science.”

This article was published as part of The Pregnancy Edit for September 2021. If you are interested in writing a blog or participating in an interview about alcohol-related harm in pregnancy for the SSA website, please contact Natalie Davies at natalie@addiction-ssa.org.

The opinions expressed in this post reflect the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official positions of the SSA.

The SSA does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of the information in external sources or links and accepts no responsibility or liability for any consequences arising from the use of such information.

Test Small

Regular Content